Top: Reclaimed Organics is a residential and commercial food scraps collection subscription service in New York City. Photo courtesy of Common Ground Composting

Nora Goldstein

The 2021 BioCycle Residential Food Scraps Collection Access Study, conducted from June-October 2021, threw out a wide net to “troll” for programs that provide households access to food scraps collection via curbside service or drop-off sites. In previous BioCycle studies on residential access, only municipally supported programs were surveyed. In 2021, the net was cast wider to include collection via subscription services offered by private, nonprofit and worker-owned enterprises.

Wilmington Compost Company’s 5-gallon container for household food scraps. Photo courtesy of Wilmington Compost Co.

Niche haulers for commercial and institutional food scraps collection emerged on BioCycle’s radar about 25 years ago . Then, about 10 years ago, we started tracking enterprises collecting food scraps from the residential sector. One of our early favorites was Carter’s Compost. Carter Schmidt was 9 years old when we interviewed him in 2014. “My dad was blogging on the computer, and he came across Bootstrap Compost in Boston, Massachusetts, a food scraps pick-up service,” said Carter. “He thought, ‘Wow that is really cool.’ We have a trailer, we have bikes, we have buckets…and he sent me on my way.” At the time, Carter’s Compost was collecting about 60 5-gallon buckets of food scraps a week and composting them in several backyards in the neighborhood.

Since then, there has been a rapid rise in the number of subscription services available for residential food scraps collection and/or drop-off. Some are bicycle-based, others use a combination of bikes and pickup trucks, and others use conventional collection vehicles, e.g, 25 cubic yard packers, customized trailers, etc. Using directories created by CompostNow, a subscription service provider operating in multiple states, and the Institute for Local Self-Reliance — as well as BioCycle data — 124 services in the U.S. were identified. This is likely an undercounting, as these services “pop up” on a continual basis.

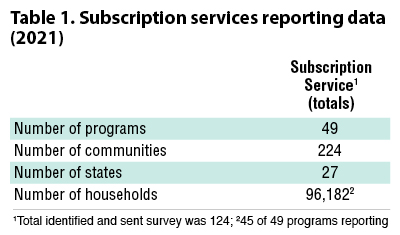

Table 1 provides an overview of the data collected. Out of the 124 services that received a questionnaire, 49 responded. Data discussed in this article (Part II) reflects those survey responses. While in theory all households within the service area of these enterprises have access, residents pay a fee to participate, which may not be affordable — and in many cases, the subscription services are small-scale and are unlikely to have the capacity to service all the households that have access.

Table 1 provides an overview of the data collected. Out of the 124 services that received a questionnaire, 49 responded. Data discussed in this article (Part II) reflects those survey responses. While in theory all households within the service area of these enterprises have access, residents pay a fee to participate, which may not be affordable — and in many cases, the subscription services are small-scale and are unlikely to have the capacity to service all the households that have access.

About 80% of the services responding offer both food scraps collection and drop-off. In some instances, the drop-off locations are at municipal facilities such as recycling centers or at farmers markets.

The top states in terms of the number of communities with collection or drop-off provided by the services surveyed are: Missouri-28; Pennsylvania-25; Georgia-23; Connecticut-21; Texas-19; and North Carolina-19. The top states in terms of households using a subscription service offering collection or drop-off are: Massachusetts and Rhode Island-25,300; North Carolina and Georgia-10,220; Pennsylvania-8,091; Connecticut-2,500; and Wisconsin-2,076. Where two states are listed together, the data reflects enterprises that offer service in both states so totals are combined.

Black Earth Compost services households with a 13-gallon collection cart (on far right). Photo courtesy of Black Earth Compost

Subscription Service Characteristics

The majority of the services responding provide both residential and commercial food scraps collection. For households, frequency of collection can be weekly, biweekly, or once a month — with the fees decreasing with less frequent collection. About 50% of the services responding to our questionnaire (out of 49) provide weekly and biweekly collection, 25% provide only weekly, and the remainder do either biweekly or once a month.

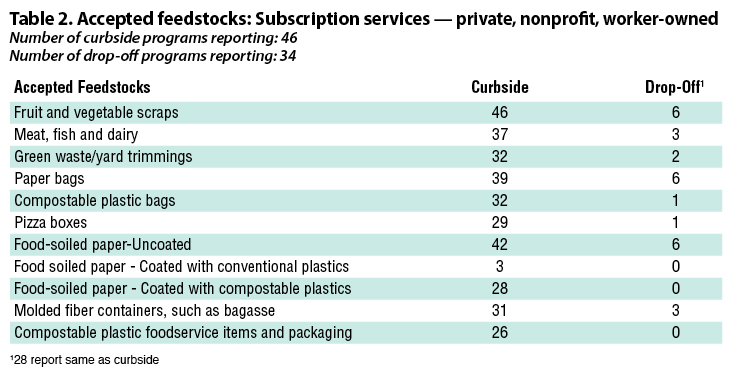

Table 2 lists the feedstocks accepted by these programs. Most take all food scraps, and the majority also accepts uncoated food-soiled paper. Of those reporting, 32 accept certified compostable liner bags. Almost every subscription service utilizes a 5-gallon bucket for collection; a few use a 4-gallon square bucket. Ten services responding offer larger sized containers, e.g., 13-gallon, 20-galllon and 32-gallon carts.

Forty of the 49 respondents answered the question about where the collected food scraps are composted. Of those, 12 do their own composting, e.g., at the drop-off location or at their farm; 27 use a municipal or private composting facility, and one uses a commercial food waste digester.

Forty of the 49 respondents answered the question about where the collected food scraps are composted. Of those, 12 do their own composting, e.g., at the drop-off location or at their farm; 27 use a municipal or private composting facility, and one uses a commercial food waste digester.

Other highlights gleaned from the responses include:

- 45 subscription services provided information about the level of contamination in the food scraps collected. Of those, 4 report no contamination, 36 report <5% contamination, 3 report <10%, and 2 report >10%. Customers with higher levels of contamination typically receive a warning and if the situation persists, are fined or are suspended from the program.

- By far, the most common reason for customers to terminate service is because they are moving.

- Only a handful of the services provide a kitchen container for collection of food scraps. Some do include a starter supply of certified compostable bags.

- When asked what the main reason(s) households have for signing up for their subscription service, the majority indicated the reasons were climate change, a desire to minimize waste, and that they could not compost at home. Others cited convenience, their civic duty, receiving compost back from their service provider, and saving money on their trash collection fee. Four respondents noted that residential food scraps recycling is required by law. Three of those enterprises are in Vermont, which banned disposal of all food scraps as of July 1, 2020. The other is in California, where a law to recycle all food scraps, including residential, takes effect on January 1, 2022.

- Collection route density was the most common pain point highlighted, followed closely by the costs of collection and the tipping fee at the processing facility. Several cited low participation, difficulty in finding drivers, and contamination. One noted that it was outgrowing its current system.

Subscription Services Takeaways

LA Compost has multiple drop-off locations in Los Angeles for residential food scraps. Materials are composted at the drop-off sites. Photo courtesy of LA Compost

Without a doubt, subscription services for household food scraps collection is a “growth industry” in the U.S. In some states, subscription services are the only providers of residential food scraps collection. The reasons why these entrepreneurs launch their services vary. For example, some start a service after relocating to a city or town with no access to food scraps recycling — something they had grown accustomed to where they lived before. Others can’t compost at home, and see a demand for collection (for people like themselves, their neighbors and friends). They launch a small-scale collection enterprise, often using a bicycle and trailer, and partner with a community garden to compost the food scraps. In several cases, enterprises are started by community gardens and urban farms as a way to increase the volume of compost they can make. In the process, they provide employment for nearby residents, including youth, who do the collection.

State mandates or bans on food scraps disposal are another trigger to launch subscription services. Vermont is a case in point. As noted above, a state law (the Universal Recycling Act) prohibits disposal of food scraps. Jurisdictions have to provide households with access to food scraps collection via curbside and/or drop-off. All solid waste transfer stations in Vermont are required to accept food scraps via drop-off. Only two jurisdictions in the state offer curbside collection. This curbside service void has created an opportunity for subscription services, which are becoming available in some areas of the state, e.g., the City of Burlington and surrounding area. In many cases, jurisdictions provide links to these services on their websites.

With increasing awareness about the contribution of food waste disposal to landfill methane emissions, and the benefits of composting and compost use, more and more citizens who can’t compost at home are seeking alternatives. This has created demand for food scraps collection and drop-off services offered by private, nonprofit and worker-owned enterprises. Frequently, municipalities embrace these services, often promoting their availability on their recycling websites, and/or asking the services to set up drop-off locations, e.g., at recycling centers, farmers markets or outside a municipal building.

Part III of the 2021 BioCycle Residential Food Scraps Collection Access Report analyzes overall trends identified in the study, and BioCycle’s next steps to continue tracking the data. Part III also includes the list of programs reporting data for the 2021 BioCycle Nationwide Survey.